Left: Heinz Rabbinic Field Representative (RFR) Frank Butler (right) and Rabbi Baruch A. Poupko of Shaare Torah Congregation, a local synagogue, inspecting a vat at the Heinz plant in Pittsburgh, 1951. Courtesy of the Detre Library and Archives, Senator John Heinz History Center. Right: OU mashgiach Rabbi Moshe Perlmutter at Allen Flavors, Inc. Photo: Kruter Photography

The opening of a kosher cafeteria on an American college campus is not the kind of news that a major US newspaper ordinarily deems worthy of coverage. But when the Orthodox Union inaugurated a kosher dining facility at Harvard in 1926, America’s most influential daily considered the story “fit to print” precisely because the Harvard administration had been, as the New York Times put it, “restricting the number of Jews” admitted as students.

That Harvard of all places would become the home of a kosher cafeteria dramatically illustrates how the phenomenal success of OU’s kosher supervision efforts has not only revolutionized kosher cuisine in the United States but also helped contribute to securing Orthodox Jewry’s place in American society.

The founder and pioneering leader of the OU Women’s Branch, Rebecca (Betty) Goldstein was instrumental in the establishment of OU Kosher in 1923. Courtesy of Aaron Reichel

The Rebbetzin (Rabbi’s Wife) and the Engineer

There is no evidence they ever knew each other, but the Barnard College–educated founder of the OU Women’s Branch and an eccentric World War I–era Chicago engineer were two of the main reasons for the rise of effective kosher supervision in modern America.

Rebecca “Betty” Goldstein founded the Women’s Branch of the OU in 1923 with a mission “to re-establish the Jewish home as a sanctuary and to recreate the Jewish mother as the priestess.” Pamphlets distributed by the Women’s Branch explained women’s ritual obligations and presented kosher as the key to developing a spiritually and physically healthy Jewish home. The Women’s Branch also published popular kosher cookbooks that made keeping kosher more attractive.

But it is hard to imagine Goldstein’s kosher education efforts succeeding without the advent of the modern home refrigerator. Enter Fred W. Wolf, Jr., a Chicago inventor known for his “eccentricities” (as one chronicler put it), who had a special interest in both race car design and refrigeration. On the eve of World War I, Wolf invented the “Domelre,” short for Domestic Electric Refrigerator. The spread of home refrigerators during the interwar years revolutionized the lives of American homemakers and their families. The new appliance greatly simplified meal preparation, made it possible to buy larger quantities of food products without fear of quick spoilage, and in general turned mealtime into a more pleasurable experience.

Betty Goldstein and her colleagues in the OU Women’s Branch recognized the urgent need to increase the variety of food products available to the women whom they were urging to keep kosher. A kosher Committee was appointed, which immediately launched a program of “making kosher products available to the housewife, products which had heretofore been

of doubtful manufacture.”1 The Women’s Branch began dispatching representatives to personally inspect food manufacturing plants.

“We had always been telling our children what they might not eat,” a member of the OU Women’s Branch wrote [see sidebar below]. “We decided, however, to see if we could persuade some of the well-known manufacturers of food products to substitute kosher for non-kosher ingredients—and then we could point out the things we were permitted to eat.”

These hands-on efforts inspired Betty’s husband, OU President Rabbi Herbert W. Goldstein, to launch the organization’s program of systematic kosher supervision. The program was to be “a not-for-profit public service free of the element of personal gain and vestment.” Moreover, the OU’s kosher certification program aimed at ensuring the growth and vibrancy of Orthodox synagogues, a central part of the OU mandate.

Crackers and Beans

Crackers and Beans

Rabbi Goldstein already had some experience in this realm, as the (unpaid) supervisor for Sunshine Biscuits, the only kosher cracker available in the United States in the early 1920s. Sunshine products appear to have been the first to be labeled with the OU’s certification, marked by an early Hebrew-language version of the organization’s insignia.

“This is the first time in the history of our country that kosher crackers are available for use in Orthodox Jewish homes, and we feel that by this accomplishment we have helped to fill a long-felt want among scrupulous and observant housewives,” the Women’s Branch proudly announced in a 1925 report.

The first major coup scored by OU Kosher was its agreement with Heinz in 1925. A visit by OU supervisors to the Heinz plant in Pittsburgh that year determined that its vegetarian baked beans, and twenty-five more of its famous 57 varieties, merited the kosher stamp of approval. Heinz products were the first to carry the now-famous mark of a “U” inside a circle. The new symbol, which is today the most widely-recognized certification mark, was designed by Heinz mashgiach Frank Butler, OU President Herbert S. Goldstein and advertiser Joseph Jacobs.

Certifying food products was not the only way in which the OU advanced the cause of kosher during those years. Thanks in part to the efforts of OU lobbyists, the New York State Assembly banned the marketing of food as “kosher” without evidence of Orthodox rabbinical supervision, and the state’s Department of Agriculture created a Kosher Law Enforcement Bureau. The OU also worked with New York City’s Department of Markets, which fielded a special unit to pursue evidence of fraudulent kosher claims, and the Manhattan district attorney prosecuted violators so vigorously that one Yiddish newspaper hailed him as “the best chief rabbi New York ever had.” While the legal authorities did what they could, the OU focused the bulk of its attention on expanding the availability of certified kosher food products. Those efforts were greatly enhanced by the establishment, in 1935, of the OU’s Organized Kashrus Laboratory. Headed by chemist Abraham Goldstein, the lab tested foods and fielded questions about the status of various products. The lab also published a quarterly Kosher Food Guide.

In the years prior to World War II, OU certification was extended to, among other notable items, Manischewitz wines (1934), Empire Kosher chicken (1938) and Barton’s Candy (1940). The latter grew to fifty stores within a decade and dominated the kosher candy market.

An Exodus and its Aftermath

The mass exodus of inner-city residents to the suburbs after World War II made the OU’s kosher supervision program an even more important part of the broader effort to combat the erosion of Jewish religious observance. In heavily Jewish neighborhoods of New York City, kosher food products were easily accessible at small grocery stores, bakeries and butchers. That was not always the case in outlying areas to which Jews relocated after the war. Ensuring the availability of a wide range of kosher products in suburban grocery stores—and, increasingly, supermarkets—was crucial to keeping on-the-fence Jewish consumers within the kosher fold.

With the OU’s kosher efforts under the leadership of Rabbi Alexander S. Rosenberg, the postwar years saw a major expansion of OU Kosher activity. Hired in 1950 as the first rabbinic administrator of the kosher Division, Rabbi Rosenberg would serve in that position until his death twenty-two years later.

At the beginning of Rabbi Rosenberg’s tenure, the OU employed about 40 full-time RFRs, certifying 184 products for 37 companies. By 1954, those numbers had increased to 78 RFRs, 300 products, and 138 plants. By 1961, there were 585 RFRs, 1,830 products, and 359 factories; by 1970, the respective figures had grown to 750, 2,500, and 475.

Historians attribute much of Rabbi Rosenberg’s success to his ability to develop close personal relationships with top executives at the manufacturers the OU supervised. Many came to relate to him “like a Hasid believes in his rebbe,” as one biographer put it. Among the many prominent clients Rabbi Rosenberg brought to the OU were Procter & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive.

Another important factor was Rabbi Rosenberg’s focus on bringing OU supervision to factories that produced the key ingredients used in many kosher foods. Increasing the number of kosher ingredients significantly expanded the number of food products that could then be certified kosher.

Rabbi Rosenberg also launched an annual OU kosher Directory, distributing more than 100,000 copies through Jewish organizations and synagogues. Such educational efforts simultaneously served the needs of the kosher community and helped created an ever-larger base of consumers. By 1970, an estimated 3,000 different kosher products were available nationwide.

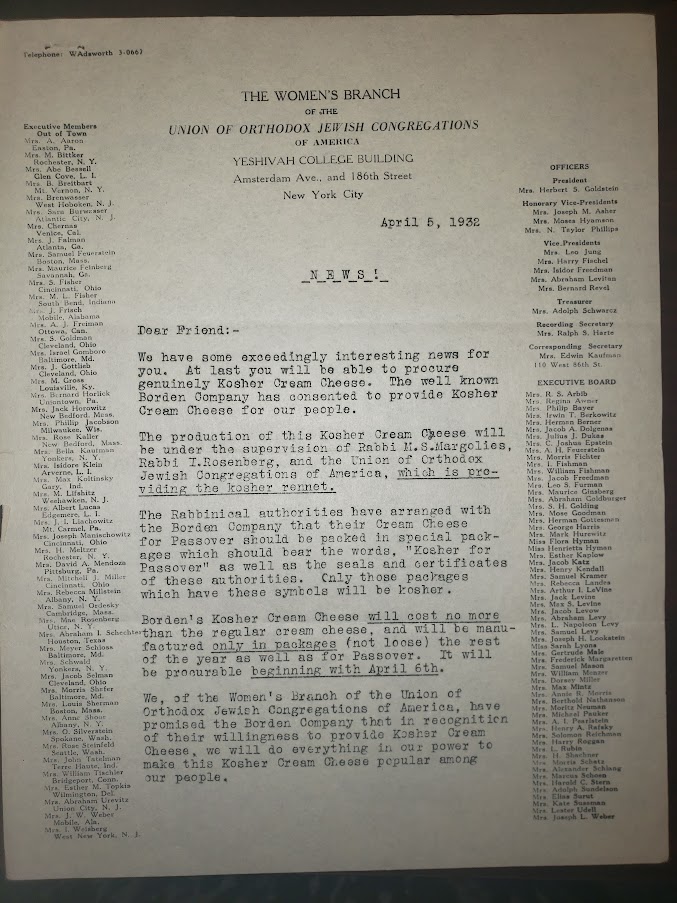

Members of the OU Women’s Branch worked hard to organize campaigns and pressure food companies to make their products kosher. They gradually convinced a growing number of companies that catering to kosher consumers would increase sales. By the mid-1930s, about two dozen companies, a few of which manufactured national brands, were OU Kosher certified. Pictured here, a letter sent from the OU Women’s Branch to its constituents in 1932. The letter states that Borden cream cheese is now kosher for Passover and that they “promised the Borden Company that in recognition of their willingness to provide Kosher Cream Cheese, we will do everything in our power to make this Kosher Cream Cheese popular among our people.” Courtesy of the Herbert S. Goldstein & Rebecca (Fischel) Goldstein Family Papers, Yeshiva University Archives

Under Rabbi Menachem Genack, OU Kosher’s rabbinic administrator since 1980, OU supervision has been extended to an almost dizzying array of major clients. Pepperidge Farms signed on in 1987, opening its famous lineup of baked goods to the Orthodox community. Coca-Cola switched its supervision to OU in 1990. They were soon followed by—among many others—Hershey’s chocolates (1994); eighty-two of Nabisco’s products, including the long-elusive Oreo cookies (1997); Dole fruits and juices in 2008, followed four years later by Minute Maid juices; the Post family of breakfast cereals switched to the OU in 2016; and Tic Tacs breath mints became OU certified two years after that. And as the popularity of meat substitutes has soared in recent years, the Impossible Burger became OU certified in 2018, a true sign of the times.

Today, OU Kosher remains by far the largest and most widely-recognized kosher certifying agency, with some 900 RFRs and managers, more than 6,000 companies, more than 1.3 million supervised products produced in 14,000 facilities in 106 countries, and a database for tracking the 2.4 million ingredients used in the foods that the OU certifies.

The Americanization of Keeping Kosher

In the first decades of the twentieth century, keeping kosher was widely regarded as an esoteric, old-world dietary regimen to which only a tiny number of consumers adhered. Even within the small American Jewish community, only a portion observed the rules of kosher. As a result, not many manufacturers regarded the kosher market as a serious vehicle for selling their products.

But gradually a snowball effect developed, as each new food that came under OU supervision provided fresh evidence of marketing opportunities. And as kosher-certified foods became more numerous and more visible, this marker of Jewish separatism increasingly became an accepted part of American culture. Making America more kosher was making keeping kosher more American.

Professor Timothy Lytton, a historian of kosher, has pointed to a subtle but important link between kosher expansion and the Americanization process. He has argued that in their development of products such as kosher imitation bacon bits, food companies are appealing to a “desire to use food as evidence of the compatibility of traditional religious observance with a typical middle-class American lifestyle.”

Increasingly, during the 1960s, ethnic groups in the United States were no longer expected to abandon their traditional ways, including their cuisine, in order to be part of the fabric of American life. Jews, too, could feel more comfortable embracing their kosher—often OU-supervised—diet.

Today, OU Kosher remains by far the largest and most widely-recognized kosher certifying agency, with some 900 mashgichim and managers, more than 6,000 companies, more than 1.3 million supervised products produced in 14,000 facilities in 106 countries, and a database for tracking the 2.4 million ingredients used in the foods that the OU certifies.

As food manufacturers came to treat Orthodox Jews as a legitimate constituency of consumers, they helped advance the process of Orthodox Jewish culinary differences being seen as a legitimate part of the American experience. A kosher option in airplane travel meal service was first offered in 1962, and would soon become the norm in that industry. Three years later, a famous series of advertisements for OU-supervised Levy’s Rye Bread featured a Native American, two African-Americans, and an Asian-American enjoying Levy’s alongside the slogan, “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s.” The ads were evidence of not only a growing tolerance for Jewish food differences, but also an increasing interest by non-Jewish consumers in certain Jewish foods.

A growing number of food manufacturers came to understand that in addition to those non-Jews who might enjoy a slice of kosher rye bread simply for its taste, there were constituencies of consumers who had more compelling reasons to patronize kosher-certified food—such as the lactose intolerant, who can rely on the “OU pareve” designation to ensure no dairy is in a particular product; individuals with allergies to animal proteins, who can rest assured that an OU-supervised dairy product could have no trace of meat in it; and Muslim consumers whose observance of halal religious dietary laws requires them to be certain that no pork could ever make its way into their food.

At the same time, the word “kosher” has gradually entered the American lexicon as a synonym for “pure” or “superior.” A certain number of non-Jewish consumers perceive kosher-supervised foods as possessing a higher level of quality. For them, the OU certification mark stands for a preferable product, religious considerations aside.

An initiative undertaken one hundred years ago to make Orthodox practice more feasible and attractive has thus not only enhanced an important component in the lifestyle that Orthodox Jews now enjoy, but has also made it more possible than ever for them to feel no conflict between being Jewish and being American.

Today, an incredible array of OU-certified products has revolutionized the dietary habits of American Jews and more than a few non-Jews. References to keeping kosher abound in the popular culture. And the opening of a kosher cafeteria on an Ivy League university campus is no longer reported in the mainstream news media—precisely because keeping kosher has become an accepted part of American life.

Note

1. Selma Freedman, “The Women’s Branch— Twenty-Five Years of Achievement,” Jewish Life, 15: 5 (June, 1948), 51-56.

Dr. Rafael Medoff is the author of more than twenty books about American Jewish history, Zionism and the Holocaust, including The Rabbi of Buchenwald: The Life and Times of Herschel Schacter (New York, 2021).