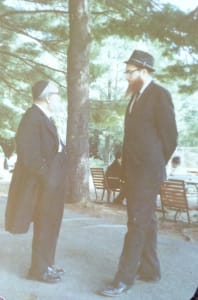

Rabbi Chaim Yisroel Belsky zt”l (right) with his rosh yeshiva, Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky zt”l, at Camp Ohr Shraga in 1969.

Last week, the OU suffered an enormous loss with the passing of Moreinu Virabeinu, Harav Hagaon, Rav Chaim Yisroel Belsky zt”l, who provided halachic and spiritual guidance to the OU Kashrus Department for more than 28 years.

The OU was not the only organization to experience an enormous loss. Rabbi Belsky had an amazing array of talents and skills, and he served in many different capacities. In each role that he played, his passing left a great void that cannot be filled.

Rabbi Belsky was an adam gadol, but even among gedolim, Rabbi Belsky was one of a kind. There are gedolim in lomdus, gedolim in machshava and mussar, gedolim in psak and gedolim in leadership. Rabbi Belsky was unique because he was a gadol in all of the above.

Rabbi Belsky was a brilliant, multifaceted and talented individual. He was first and foremost an extraordinary talmid chochom. He had mastery over every aspect of Torah, including esoteric and obscure areas that few others knew and understood. He was as much at home in Keilim and Kinim as he was in Baba Metzia and Baba Basra. He had tremendous intellectual curiosity and was self-taught in many different disciplines. He had a strong grasp of mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, anatomy, botany, zoology, musicology, food technology and history, all of which he used for the benefit of Torah study. The legendary story of Rabbi Belsky, gazing at the stars together with his talmidim in Camp Agudah, is well known. He suddenly expressed surprise at seeing a star in the sky that he had not noticed before, and a call to NASA the next day revealed that it was a star that is only visible on rare occasions. I was once standing with him when classical music was playing in the background. Rabbi Belsky loved music and wanted to be a musician in his youth. Without batting an eyelash, he began humming the bars of the symphony and identified the composer and the exact name of the piece.

Rabbi Belsky was a mohel, shochet, menaker, baal menagen, baal koreh and baal tefillah. He was a baal hashkofa (he often invited his talmidim to ask him any question that troubled them), a darshan and a baal mussar (his talks were always relevant, compelling and down to earth, and he spoke to the heart with eloquent simplicity). Rabbi Belsky authored seforim in the areas of halacha and agada. He wrote eloquently in Loshon Kodesh and in English, and he could write in classical style or wax poetic. (He read Homer’s Iliad at age five.)

To appreciate the breathtaking array of Rabbi Belsky’s talents and strengths, consider the amazing diversity of positions that Rabbi Belsky held and the critical role that he played in each.

There was Rabbi Belsky, the maggid shiur in Torah Vodaath. Starting at the young age of 25, he was a Rebbi for over 50 years and delivered brilliant and masterful shiurim. As a Rebbi, Rabbi Belsky never wrote off any student and he believed in every talmid. He admonished Rabbeim that if a student fails, it is often because the Rebbi was not proud of the talmid, or worse, because the Rebbi wrote him off. Rabbi Belsky’s unlimited love and devotion for each and every talmid was legendary and beyond description.

Then there was Rabbi Belsky, the Rosh Yeshiva of Torah Vodaath, for the last five years of his life. What a fitting culmination to the 72 years he spent in the yeshiva, from early childhood on.

There was also Rabbi Belsky, the Rav of Camp Agudah and the head of the masmidim program. More than simply delivering shiurim, Rabbi Belsky was a super-Rebbi, mashgiach and counselor rolled into one. He spent the entire day with his beloved talmidim as he bonded with them and taught lifelong- lessons. He travelled with them to Niagara Falls and went on other camp trips, all the time inspiring his talmidim. Canoeing down the rapids, he would point out unusual animals and plant life, and at bonfires and barbecues he regaled the masmidim with inspirational stories and nigunim of old. He took spellbinding nature walks and gave amazing guided tours of the stars and constellations to his talmidim, so they would appreciate Hashem’s magnificent world.

Rabbi Belsky, the dayan, tackled some of the most difficult and contentious dinai Torah.

Rabbi Belsky, the leader of the Vaad Lihatzalas Nidchai Yisrael and the Nasi of the Russian Kehilla, devoted himself to helping Russians reclaim their religious heritage. In an amazing show of brilliance and sensitivity, Rabbi Belsky mastered Russian so that he could converse with Russian immigrants in their native tongue.

Then there was Rabbi Belsky, the friend of umlolim, unfortunates, who were overwhelmed by the tzoros and challenges of their existence. Somehow, people from all over America, with major problems, found their way to Rabbi Belsky’s doorstep. Though he was a person of great stature, he was warm and embracing, easily approachable, with no airs or ego. In spite of his overwhelming responsibilities, he would not turn anyone away and would offer whatever assistance he could provide. I am a communal Rabbi, in addition to working in the OU Kashrus Department. Collectors of funds often showed me letters of approbation from Rabbi Belsky, attesting to the veracity of their claims. I was amazed that Rabbi Belsky wrote the letters as if he was a close family friend for many years. Recently, a woman came to my house, showed me a letter from Rabbi Belsky, and said, “Rabbi Belsky knows all my problems, loves my family and is like a father to us.”

Finally, for the past 28 years, there was Rabbi Belsky, the Senior Posek for the OU. Although that was his official title, to describe Rabbi Belsky simply as a “posek for the OU,” does not do justice to his pivotal role and major contributions to the OU.

When Rabbi Belsky came to the OU in 1987, the OU was in the midst of an unprecedented period of growth and expansion. In just a few years, the OU went from being a small agency to supervising over 1,000 companies. Because the growth was so rapid, the OU was at a critical point, where a solid halachic foundation was essential. To properly supervise the wide spectrum of food companies, (which has now grown to 9000 factories in over 80 countries around the world,) numerous halachic issues needed to be addressed and policies had to be formalized. The OU was fortunate to have two gedolai Yisrael, Rav Yisrael Belsky zt”l and yibadel lichaim, Rav Herschel Schachter, shlit”a, working in concert under the direction of Rabbi Menachem Genack, to formulate a halachic platform upon which the entire OU supervision operates.

This effort was a monumental task. To appreciate the scope of this endeavor, it should be noted that for the past 28 years Rabbi Belsky and Rabbi Schachter visited the OU office in Manhattan on a weekly basis (on separate days) to render halachic decisions for the Rabbinic Coordinators and Rabbinic Field Representatives. About 20 years ago, the OU recognized the importance of recording these piskai halacha, and established a position of safra didayna (court recorder) to document the decisions of the poskim. To date, there are thousands of teshuvos and psokim stored in the OU database. These documents cover the entire gamut of every aspect of industrial production and food service, and they serve as the basis for all OU certification.

Establishing this massive halachic platform was a great challenge. A prerequisite for a psak halacha is having a clear understanding of the metzius (the reality) under discussion. If one does not understand the modern techniques for growing microbes on mediums (which are often not kosher) to produce enzymes, one cannot competently discuss the relevant halachic considerations of maamid, nishtaneh and zeh vizeh gorem. Rabbi Belsky was uniquely suited to the task. There was no one like Rabbi Belsky, who combined a total mastery of the intricacies of halacha, and a profound understanding of the complexities of modern food production.

Furthermore, the classical poskim did not deal with the new realities. One will not find a teshuvah from the Nodah Biyihudah or the Chasam Sofer about genetically modified tomatoes (GMO) with gene splices from a pig, and the process of finding precedents in classical halachic literature requires great skill.

Finally, it is not difficult to research a sheilah and find multiple positions among the poskim. The challenge is to decide which poskim to follow. This requires the shikul hadaas (balanced judgment) of a posek to decide when to be machmir, when to be maikil, which opinions to follow and which to reject. This process was all the more complex for the OU, the world’s largest kashrus organization, because The OU poskim were establishing a standard of kashrus for all of Klal Yisroel. Virtually all supervisions rely on the OU for ingredients. Furthermore, the OU is a trailblazer and sets a standard for many hechsherim around the world. Rabbi Belsky understood this well, and in conjunction with Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Menachem Genack, Rabbi Belsky formulated standards that he felt were appropriate for OU supervision and the entire Jewish community.

Rabbi Belsky’s approach to halacha was balanced and measured. He was not swayed by public opinion. In addition, he refused to react to the latest “tumult” before he personally investigated the facts. Over the years, there were questions raised about the kosher status of cows and milk (because of puncturing the stomach to correct a problem called Displaced Abomasums), eggs (because of the toe structure of Leghorn chickens), fish (presence of worms), water (presence of crustaceans called copepods) and the like. I asked Rabbi Belsky if we should take a stringent position while an investigation was underway. Rabbi Belsky said, “No, you don’t prohibit things that were always assumed to be kosher, unless you are certain that the situation has changed.”

In addition to charting a halachic path for the OU, Rabbi Belsky provided constant inspiration, encouragement and direction. Rabbi Belsky noted that kedusha requires persistent shemira (protection) because it is so easily corrupted. He referenced the requirements of shmira for terumah and the mikdash detailed in Parshas Korach (18:1-8). Rabbi Belsky explained that just as the Leviim were responsible for the shmira of the mikdash and terumah, so too the Rabbinic staff at the OU are shomrim, who guard and protect the sanctity of Klal Yisrael, by insuring the kosher integrity of food and preventing timtum halev. Rabbi Belsky often remarked that a Kashrus agency must constantly seek ways to improve and enhance its supervision, both in terms of implementing stronger controls as well as upgrading halachic standards. Rabbi Belsky encouraged the Rabbis at the OU to treat a supervised plant like a sugya of the gemorah; one must study and analyze it, in depth, repeatedly, until one has mastered all aspects of the operation, and all halachic elements of supervision have been identified and addressed. I recall Rabbi Belsky saying on many occasions that the word “bidieved” is traif in the hallways of a Kashrus organization, and hashgacha must be “lichatchila.” Furthermore, he would say that a hashgacha should not be limited to satisfying the requirements of the Shulchan Aruch, but must go above and beyond the letter of the law.

In addition to charting a halachic path for the OU, Rabbi Belsky provided constant inspiration, encouragement and direction. Rabbi Belsky noted that kedusha requires persistent shemira (protection) because it is so easily corrupted. He referenced the requirements of shmira for terumah and the mikdash detailed in Parshas Korach (18:1-8). Rabbi Belsky explained that just as the Leviim were responsible for the shmira of the mikdash and terumah, so too the Rabbinic staff at the OU are shomrim, who guard and protect the sanctity of Klal Yisrael, by insuring the kosher integrity of food and preventing timtum halev. Rabbi Belsky often remarked that a Kashrus agency must constantly seek ways to improve and enhance its supervision, both in terms of implementing stronger controls as well as upgrading halachic standards. Rabbi Belsky encouraged the Rabbis at the OU to treat a supervised plant like a sugya of the gemorah; one must study and analyze it, in depth, repeatedly, until one has mastered all aspects of the operation, and all halachic elements of supervision have been identified and addressed. I recall Rabbi Belsky saying on many occasions that the word “bidieved” is traif in the hallways of a Kashrus organization, and hashgacha must be “lichatchila.” Furthermore, he would say that a hashgacha should not be limited to satisfying the requirements of the Shulchan Aruch, but must go above and beyond the letter of the law.

Rabbi Belsky was a moral compass of the OU. He prodded the OU Rabbonim to oversee kashrus with yashrus and integrity. Not only were we privileged to ask Rabbi Belsky sheilos related to Yoreh Dayah (which details the laws of kashrus), but we had the opportunity to ask questions on Choshen Mishpat (monetary laws) as well.

Following are two beautiful stories about the moral clarity that Rabbi Belsky provided.

About 25 years ago, an OU mashgiach invited me to the wedding of one of his children in Detroit. I felt it was important that I attend, so that a member of the OU office staff would be present at the wedding. However, the flight to Detroit was a significant expense.

In the standard OU contract with companies, there is a clause that stipulates that the Rabbinic Coordinator for each certified company may visit the plant once a year at his discretion and the cost will be covered by the company. I was responsible for an OU plant in Detroit that manufactured frozen dough. I thought I would visit the plant and ask them to cover the cost of the trip, and then attend the wedding. However, I was concerned that perhaps it was not ethical to piggy-back my attendance at the wedding with an inspection of a plant that was paid for by the company, particularly since my visit to the plant was only a pretense to go to the wedding. There were only three simple ingredients in the frozen dough. Were it not for the wedding, I would never make such an unnecessary visit. (We had an on-site mashgiach who was visiting regularly.) I asked Rabbi Belsky if it was ethical, under these circumstances, to visit the plant and bill the company for the expense.

Rabbi Belsky responded that it was certainly appropriate. He said, “Each and every plant should be visited every now and then by the New York Rabbinic Coordinator because you never know what you will find. You must go, even if you have no wedding to attend. Since you should make the visit in any event, it is perfectly appropriate to schedule the visit when you have a wedding.”

Though I thought the visit was superfluous, I accepted Rabbi Belsky’s psak. Indeed, when I visited the plant there was very little to see, as the ingredients were only flour, water and yeast. As I was leaving the facility, a label caught my eye. All the other labels had the name of the manufacturer clearly displayed next to the OU, but this particular label was nameless. I asked the plant manager why the label was printed in that manner. He responded, “Oh, we plan to send these new labels to supermarkets. When they will bake-off the frozen dough in their ovens, they will apply these genetic labels with the OU.” I was stunned. This was a major kashrus concern, because the dough would be baked in non-kosher ovens. I immediately explained this to the plant manager, and I had him destroy the labels.

Afterwards, I thought that Rabbi Belsky’s words were prophetic. “You never know what you will find.” How very true.

Here is the second story which beautifully demonstrates Rabbi Belsky’s sensitivity to each individual.

A plant in the Midwest required full-time supervision. We had no one near the facility to provide supervision, and I arranged for a mashgiach to travel from the east coast. The mashgiach flew out every Sunday, and returned home erev Shabbos. This was a big hardship, but the mashgiach needed the income. My instructions to the mashgiach were that he stay at the plant daily from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM. In addition, I asked him to occasionally visit the plant in the evening. All was fine and well until one year later when I received a bill for $14,000 for night visits. I was shocked and asked the mashgiach what the bill was for. He replied that he spent four hours in the plant every evening. I told him that I had only asked him to visit on occasion, and he said he thought I wanted him to spend hours there every night. This was clearly a case of a gross misunderstanding. I felt badly for the mashgiach and asked Rabbi Belsky what to do.

Rabbi Belsky said that technically the OU owed the mashgiach nothing for his night work. Nonetheless, the OU should pay the mashgiach $5000 because one must act lifnim mishuras hadin, beyond the letter of the law. The mashgiach invested an enormous amount of time and energy, and would feel hurt and betrayed if he came away with no pay. I expressed surprise, and said I thought that lifnim mishuras hadin is optional. $5000 seemed like a large sum to pay under such circumstances. Rabbi Belsky responded that lifnim mishuras hadin is not an option. It is a requirement, as is clear from an explicit source in Bava Metzia 83a.

The gemara relates that Rabbah Bar Bar Chanah hired porters to carry barrels of wine. They apparently were not very competent. They dropped the barrels and broke them. The porters came to Raba and asked to be paid. They said they were very poor, had worked hard all day, and now they had nothing to show for their efforts. Raba felt that the porters owed him money for the damage and certainly he would not pay them for a job not properly done. The workers went to Rav with their complaint. Rav identified with the plight of the porters, who were indigent, and had tried their best. Rav instructed Rabba Bar Bar Chanah to make the payment, because one must act lifnim mishuras hadin. Rabba Bar Bar Chanah was surprised and said, “Dina hachi?” (Is this a din, a halachic imperative?) Rav responded, “Yes, it is a din”, and quoted a verse in Mishlei from which we derive the concept of lifnim mishuras hadin to support his ruling.

Rabbi Belsky turned to me and said, “You see, it is a requirement to act lifnim mishuras hadin, and the OU should pay the mashgiach at least part of his fee. He worked hard for an entire year and should not come away with nothing for his efforts.”

When Rabbi Genack heard Rabbi Belsky’s recommendation, he countered, “The OU is a communal organization and funds are mammon hatzibur. Perhaps lifnim mishuras hadin does not apply to mammon hatzibur.”

Rabbi Belsky had a tremendous repertoire of stories, and responded to Rabbi Genack’s comment with a terrific story.

Years ago, Rabbi Belsky met a 90 year old Rabbi in South Dakota who had studied in yeshivos in Europe before World War ll. The Rabbi from South Dakota (I’ll refer to him as RSD) told Rabbi Belsky the following story:

When he was a young man studying in Europe, he heard that Rav Leib Vilkomir was visiting the city of Ponevezh. Rav Leib was a great talmud chochom, and RSD wanted to meet him and discuss Torah topics. RSD traveled to Ponevezh and met Rav Leib and had a pleasant conversation. After a while, Rav Leib told RSD, “Come with me, I must go visit the Rav of Ponevezh and appease him.”

What had transpired? The Jewish community of Ponevezh owned a bathhouse, and at some point, they sold it to a certain man (let us call him Chaim Yankel) to raise needed funds. Chaim Yankel operated the bathhouse for a year and lost money, at which point he asked the community to refund his payment and take back the bathhouse. Chaim Yankel claimed that, in spite of enormous effort on his part, he could not make a profit on the business because of inherent deficiencies in the business, which had not been revealed to him in advance. The community had a different viewpoint and believed that he lost money because he was a poor businessman and they were not at fault. The community brought the matter to the Rav of Ponevezh, and he concurred that the community was not at fault. Nonetheless, as Rav of the city, he had a conflict of interests and could not rule on the matter. Rav Leib Vilkomir was visiting Ponevezh at the time and the Ponevezher Rav suggested that Rav Leib adjudicate the Din Torah between Chaim Yankel and the community of Ponevezh.

Rav Leib acquiesced and, to everyone’s surprise, he ruled in favor of Chaim Yankel. The Ponevezher Rav was very upset at the ruling, and it was for that reason that Rav Leib went to appease the Ponevezher Rav, with RSD in accompaniment.

When Rav Leib and RSD entered the home of the Ponevezher Rav, they saw that the Rav was quite agitated as he paced back and forth in his study. “Rav Leib!” exclaimed the Ponevezher Rav. “How could you rule as you did? Show me one source to support your psak in the Din Torah.” Rav Leib responded, “Why, there is a mitzvah to act lifnim mishuras hadin. Chaim Yankel worked very hard to run the business, and he believes it was not his fault that he did not see a profit. Din (justice) would dismiss Chaim Yankel’s claim, but lifnim mishuras hadin obligates you to deal with him with compassion and concern.

The Ponevezher Rav questioned Rav Leib’s logic. “What you are saying would be true if this was a private matter, but this is kehillisha gelt (communal funds) that would have been used to support widows and orphans. What right do you have to impose a judgement based on lifmin meshuras hadin at the expense of widows and orphans?” Rav Leib responded, “Lifnim meshuras hadin is a fundamental Jewish value. Punkt azoi (just as) a community must put aside money for widows and orphans, so too they must set aside money for lifnim mishuras hadin”.

Rav Belsky concluded that Rav Leib’s comment reflects the fact that lifnim mishuras hadin would apply to the OU as well. Based on Rabbi Belsky’s recommendation, the OU paid the mashgiach a substantial sum to satisfy the requirement of lifnim mishuras hadin.

Finally, Rabbi Belsky taught us Hilchos Derech Eretz in word and by example. Rabbi Belsky was mechabed every person, no matter what his stature was. I often remember Rabbi Belsky joining meetings where there was enough tension to slice the atmosphere with a knife. As soon as he entered the room, everything changed. In part, it was because he commanded respect by his mere presence. But mostly it was because he treated everyone with great respect, and that put each person at ease, and immediately diffused much of the tension. Not infrequently, we dealt with some very difficult people, but Rabbi Belsky was able to win over everyone with his charm, smile, and authentic kovod habriyos.

Rabbi Belsky told me that all relationships in life are based on respect, be it a Rebbi-talmid, general friendship or husband and wife. This simple but elegant thought reflected Rabbi Belsky’s world view, and it was by these principles that he lived his own life.

We, at the OU, had the enormous zechus of having Rabbi Belsky provide guidance to us for 28 years. His impact was immeasurable. 28 in Hebrew is כח, which means strength. In his moving hesped, Rabbi Genack spoke about Rabbi Belsky’s amazing courage. He was an ish ho’emmes (man of truth), who was not afraid to take controversial stands when he was convinced that it was the right thing to do. Rabbi Belsky was a man of כח, strength of character and conviction. By the same token, for 28 years, Rabbi Belsky infused כח, clarity, and strong moral conviction into the fiber OU kosher supervision. We were so very fortunate to have a giant in our midst.

Alas, Rav Belsky zt”l is no longer with us. Just as Rav Belsky is irreplaceable in every other capacity where he served with distinction, so too at the OU. There is no one like him. מי יתן תמורתו (who can be his replacement)?

יהי זכרו ברוך !

by Rabbi Yaakov Luban

Executive Rabbinic Coordinator